I recently ran into an old colleague and friend who works at a big retail brand (let’s call it BRB) as an IT PM. He enquired if I was still working with Yarra Valley Water, to which I replied that I had moved on and was looking for a new gig. He suggested applying for upcoming PM roles at BRB. I, however, expressed my desire to continue in my field of Agile Coaching rather than sidestepping into project management. He remarked that Agile had become a bad word at BRB and no one liked using it. He attributed the negative brand image of Agile to poor implementation on some projects by an “Agile person”. Due to his paucity of time (he had just stepped out from work for a coffee), we quickly wrapped up our conversation and agreed to catch-up again. But our conversation was enough to crystallise the thoughts I had already had in my mind (albeit on the back burner) about the way Agile is going (or being taken).

I have seen a few bad implementations of Agile that have caused stakeholders to develop a sort of PTSD towards Agile and everything that it advocates. I agree that perhaps they didn’t have the right person coaching them but the failure to deliver the right outcomes could be attributed to many causes (and mostly a mix of them):

1. Lack of expertise

If I had a dollar for every time I came across a fake “Agile Coach”, I wouldn’t need a full time job! I have seen so many charlatans in the name of Agile Coaches that it’s understandable to see people doubting their trade. When you invest in someone who is not an expert and doesn’t know how to deliver outcomes or is unable to see the big picture, you’ll end up with sub-optimal solutions at best or a mess for someone else to clean up after later. ScrumMasters, Delivery Leads, Agile PMs might be great at what they do, but they aren’t Agile Coaches. Yes, they can definitely become one of the best coaches over a period of time but expertise requires, amongst others, effort, commitment, and a resolve to stick to the principles.

And please allow me to a bit controversial here. Whilst some consultancies are great at providing valuable solutions, not everyone is specialised in Agile. I have come across consultancies that didn’t have much Agile experience but knew the jargon because they had worked in Agile environments before. The people that they deploy at organisations are just consultants in that they have broad experience but not necessarily the depth required. I remember working with consultants who were brought in to do Agile Transformation who didn’t even attempt to address the lack of Agile mindset at the client organisation. They were consultants who had wound up at this consultancy and were sold as Agile consultants to the client. At one of the organisations I had worked for, a senior member of the leadership team sent an email addressed to the other members saying “we do not need servant leadership outside of Agile”. This clearly demonstrated a lack of the right mindset and the transformation consultant did absolutely nothing to address it. They were just focussed on getting more people billing and extending their contract.

2. Lack of environmental support

Agile doesn’t just happen. And it’s hard to make Agile work in isolation when it has connected parts that aren’t functioning in an Agile manner. Yes, you can get some benefits for sure but if you continue to drive the overall system in the old way, you will not get significant improvements. If you are still feeding requirements the old way, still using your Gantt charts to measure progress (I remember working with this programme director who was using a Gantt chart to track the delivery of user stories and plan for next ones), asking for powerpoint reports, not providing opportunities to generate feedback from delivered output, running a command and control shop, then you don’t have an Agile workplace.

3. Lack of organisational mandate

This point is related the one above but still deserves a separate mention. I have experienced departments and divisions trying to do Agile without an overall organisational mandate just because it’s the new buzzword (well, not so new anymore) or you see your competitors doing it or because it attracts better talent. Whilst there is scope for an experimental approach towards Agile to see if it will work for you or not, lack of an organisational mandate will always run the risk of not getting enough environmental support to drive it well, reverting to old practices because this isn’t working out, or people simply refusing to change their way of working. This is why “new way of working” is becoming a popular paradigm with organisations committing to doing things better. However, it has it’s own pitfalls as well which I will save for another day.

4. Solving a problem that doesn’t exist

This needs to be said. If it ain’t broken, don’t fix it. Yes, Agile offers great benefits that go a long way in supporting your organisation and addressing the needs of the customers better but if you are getting what you need with your existing system, you may not necessarily need to change to Agile.

Having looked at why Agile may not be working for some organisations, it is all the more relevant in today’s day and age.

- The markets are getting more and more competitive

- The rate of delivery to customers is increasing all the time

- Customers are jettisoning products and services quickly that don’t solve their real problems

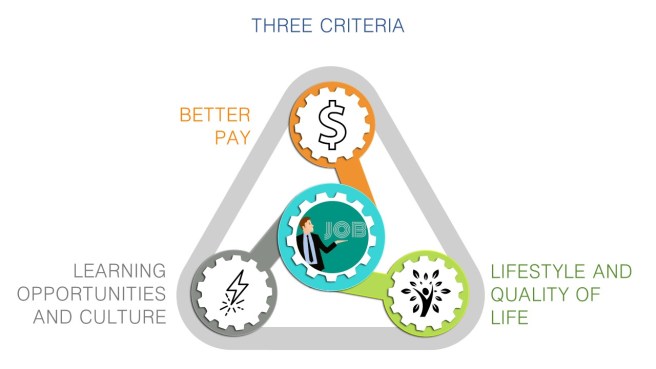

- Employees are prioritising work culture and quality of work life over other perks and remuneration

- Organisations that have had a significant presence in the market for decades are getting over taken by new age businesses

- New markets are coming up that hadn’t been envisaged before

Agile doesn’t solve all your challenges. It is not a panacea. However, it will help you navigate your way through your problems. It will help you do things well based on real feedback that will keep you focussed on the real pain points. And it will help you flag issues early on that might become a setback later. It will help you foster a culture where your employees buy in to your vision and work with you on your problems. However, it still requires making the hard yards and real experts to guide you on your journey.

Photo by Clément Falize on Unsplash